The Landing Project (LAP) found its origins in a 3” x 5.5” x 14.75” post office (PO) box. LAP is the negative space of a PO box in physical form. It is the poor woman’s Rachel Whiteread. It is the repository of the junk mail of others who came before me, as well as my own. It is the recipient of, since 2013, almost eight years of rent money. It is my New York address. It is a space of potential. It is a microcosm of the studio, or a tiny extension of my studio (now based in Philadelphia). I keep renewing it though I have not been there since before the start of the pandemic, since before the birth of my daughter. Every three months, it automatically renews and I think: is this the last time?

Now it is 2021 and the post office, seemingly the most docile of institutions, has—barely—survived the attack of 2020. Mail delivery became a battleground in the midst of an election season during a pandemic where mail-in ballots would tip the balance. Post office workers are being recognized as unsung heroes. In October, I saw children dressed up as postmen and women for Halloween. Postmaster General Louis DeJoy, instated in spring 2020, now may be called to testify for actions (or lack thereof) that interfered with mail-in ballots. In the midst of it all, paying for my PO box felt like tithing as a member of the USPS faithful.

At first, I rented the PO box in Manhattan for pure function. I needed a stable address for mail. I rented the box at a post office on Canal Street, located a few blocks from the design studio where I was working in Tribeca and across the river from a couch I was subletting in Greenpoint during those first months in New York. As that need changed, function shifted to an interest in form. LAP is one brick, one block of space in this network that exists for us to move through and fill up. What could one block of space provide, symbolize, or contain? In a way, it is a distilled version of my walks.

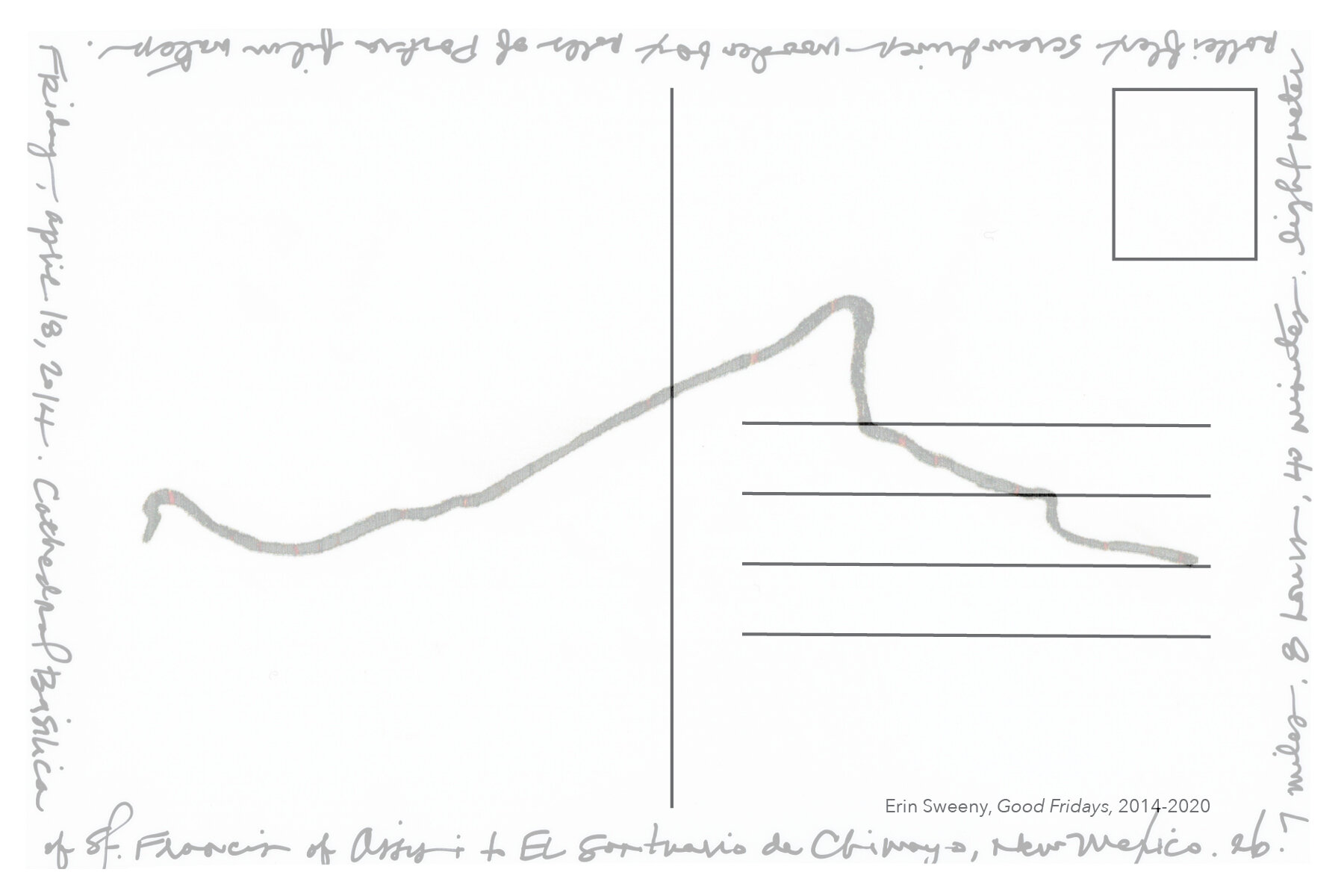

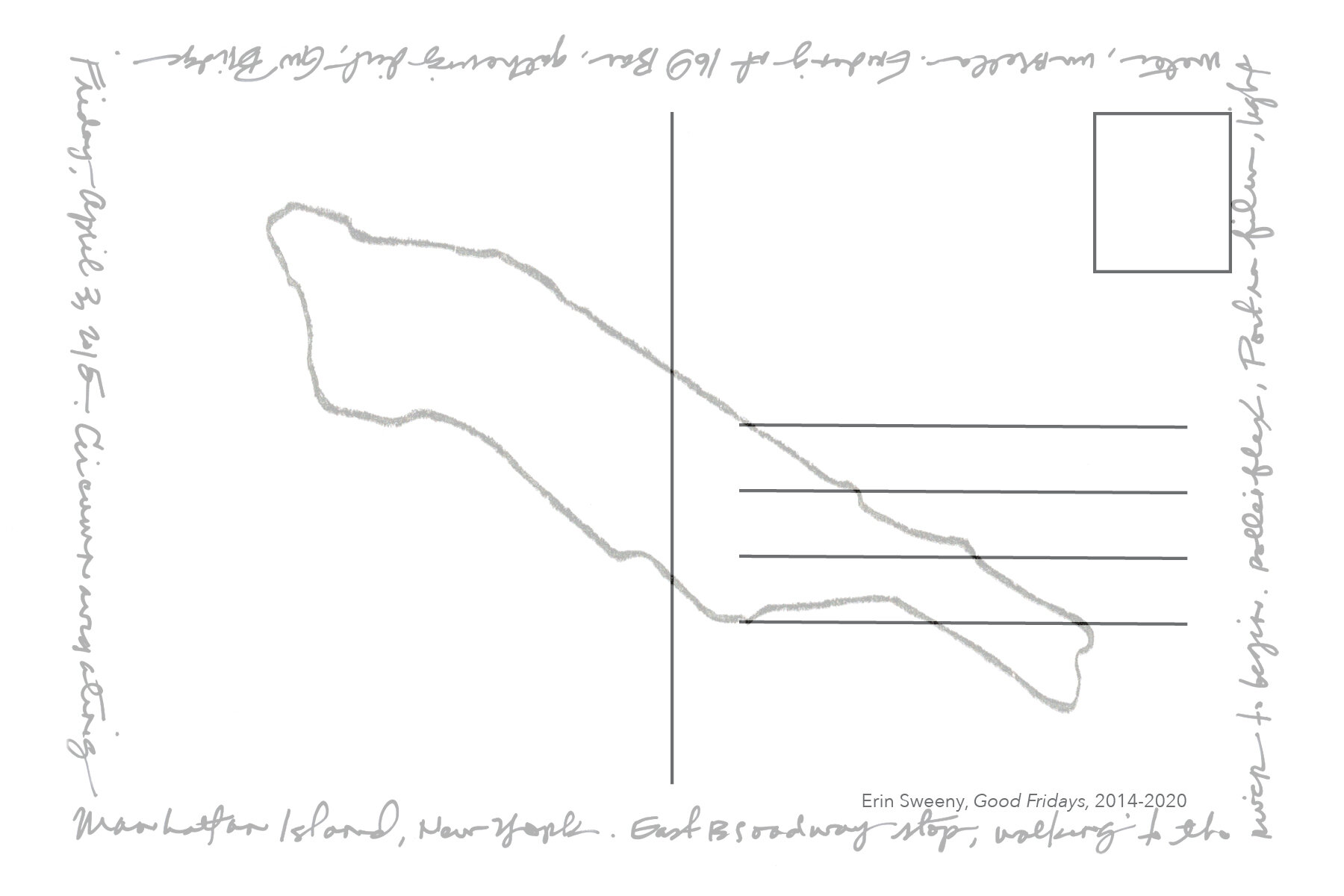

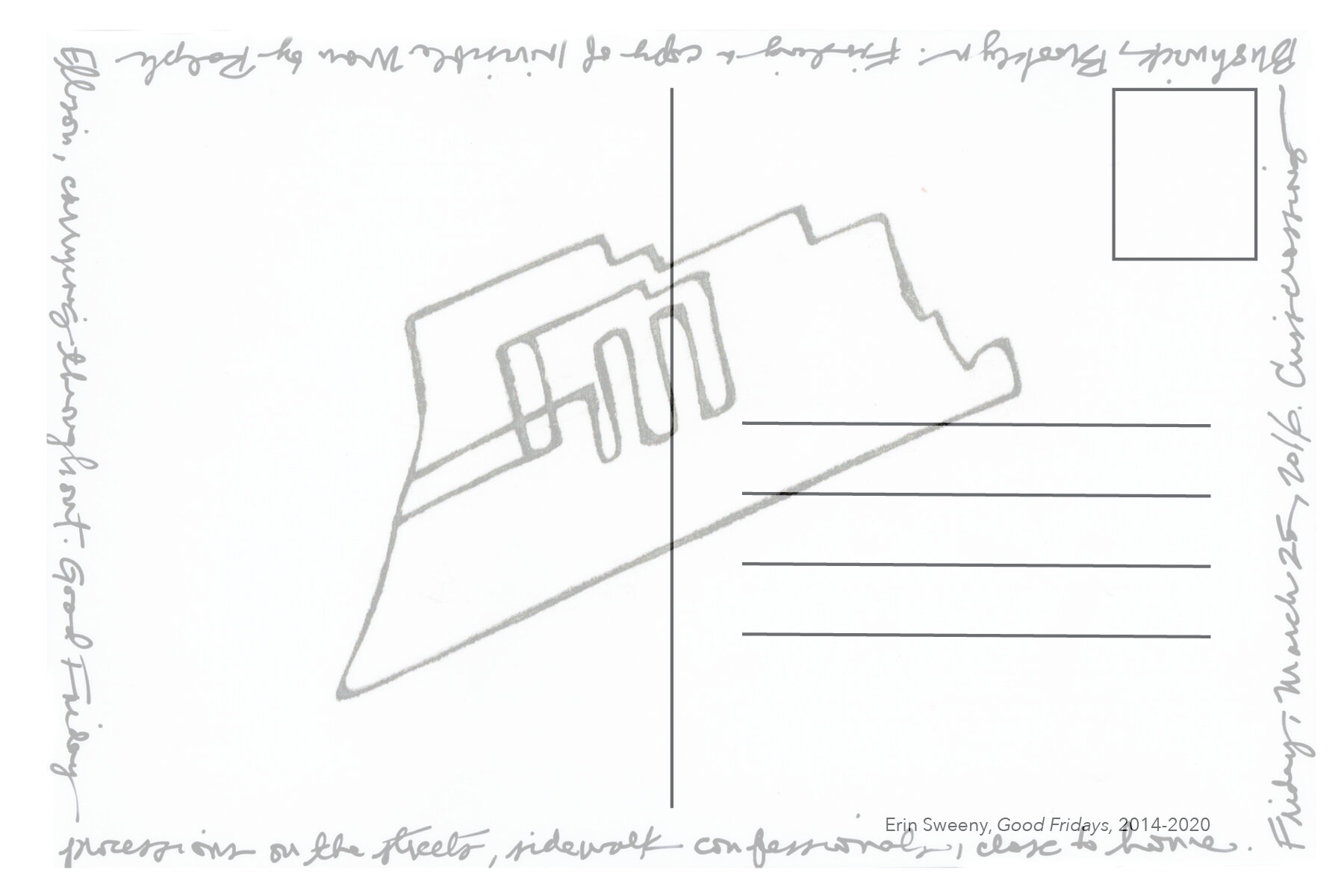

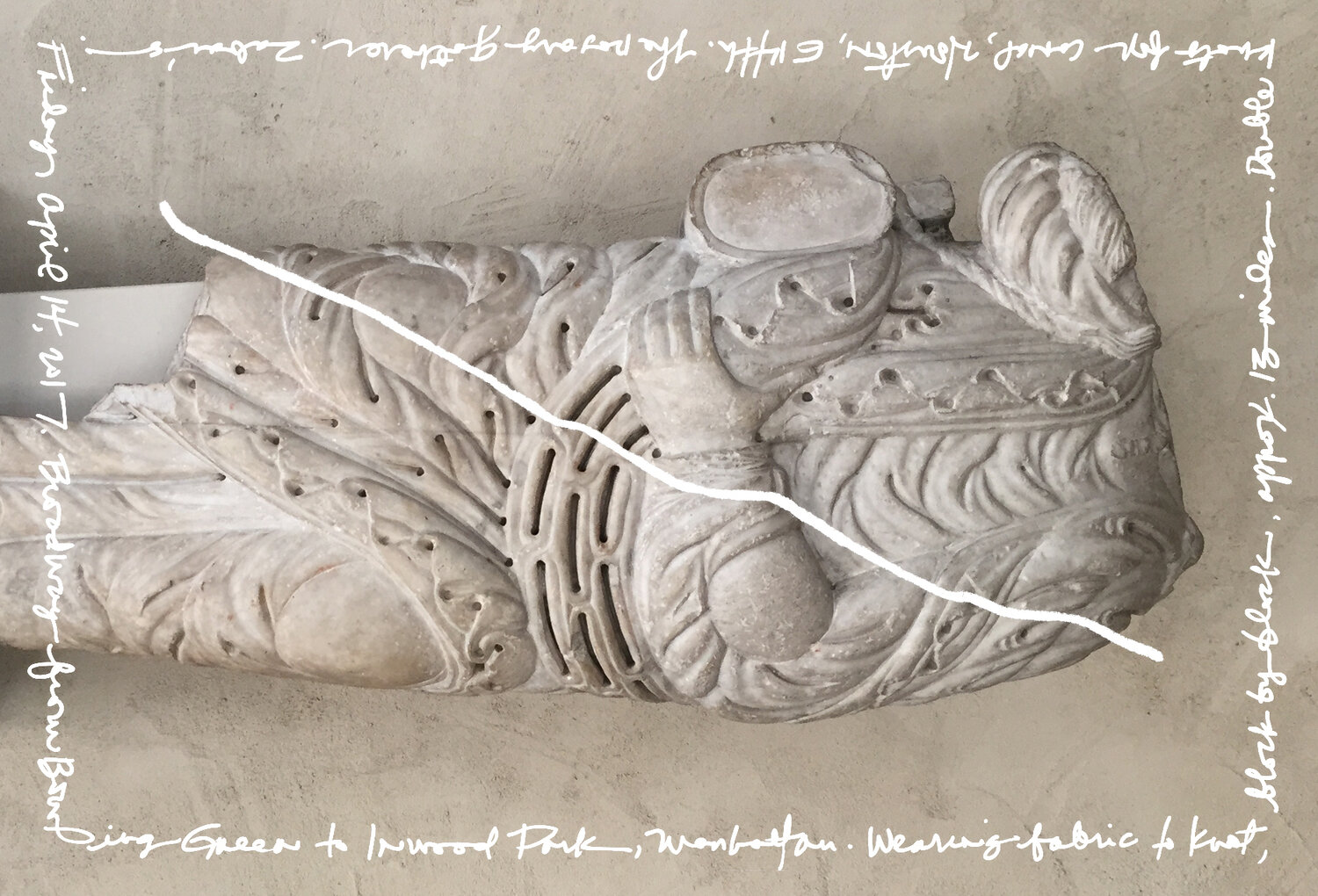

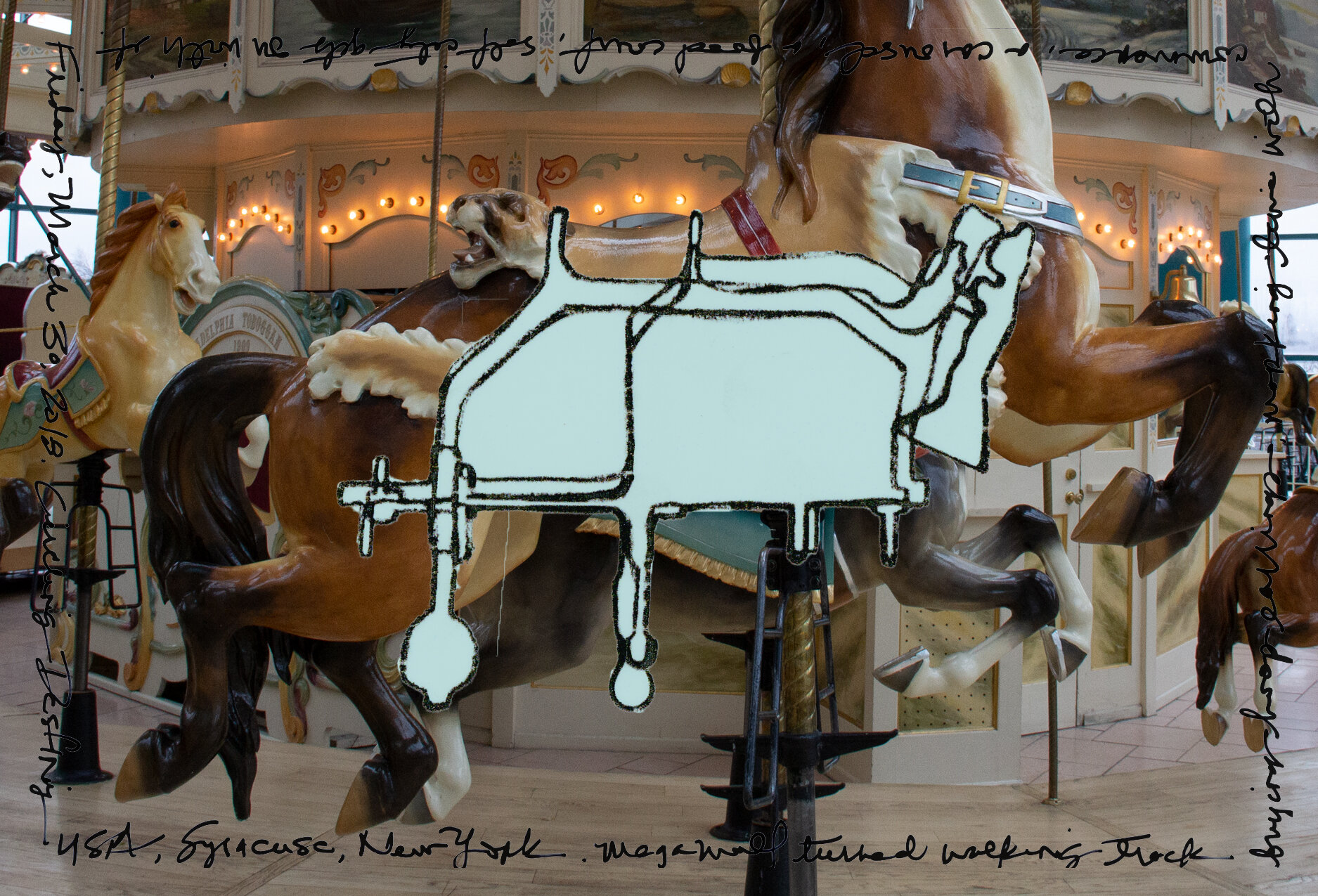

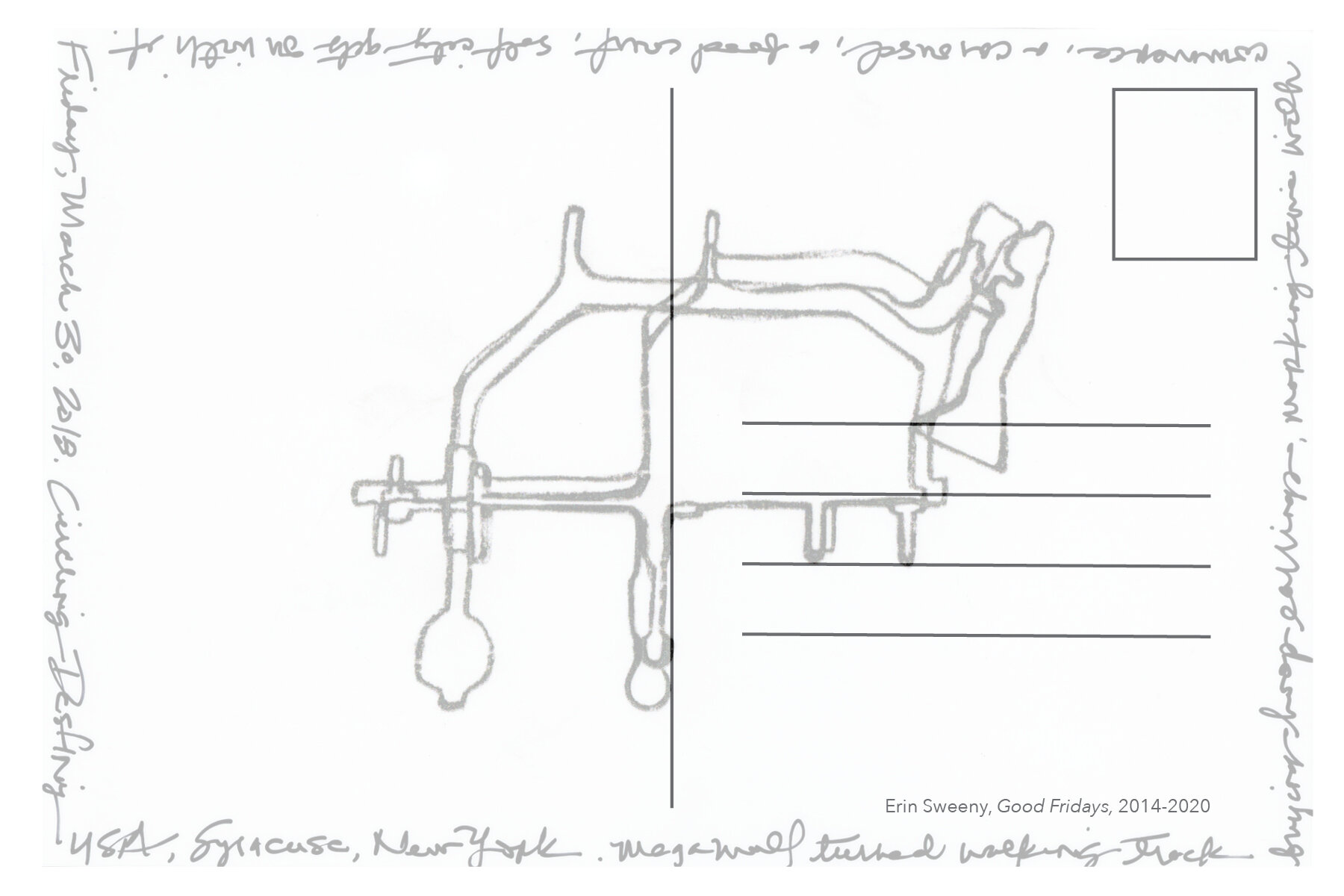

Good Fridays, a project I started in 2014—not long after renting the PO box—is focused on walking. More specifically, it is focused on a yearly walk on the moveable feast of Good Friday, and the other 364 days of the year are for responding to what happened, and how that might impact the next iteration. It is about slowing down, making space, taking time. It is about ritual for the agnostic, for the curious, for the restless. It is about the ability to move, which I know is a privilege. Most importantly, it is about bearing witness to the layers and realities of place. I think the walking, ultimately, is in service of all of the other days. These walks provide a reference point, a heightened awareness of what it feels like to move in the world when that is the central focus: to feel the particular kind of exhaustion in one’s body that comes with sustained walking, but also to remember the lives in motion witnessed. I think about those days often in this time of Corona, of restricted movement, of being a new mother with a different kind of exhaustion, of walking for two, of my little one almost walking on her own. One foot in front of the other.

It is now, truly, that I think this series of walks has ‘landed.’